A programmer's approach to the JLPT N3

In this post I'll share my experience preparing for the JLPT as a programmer.

In early 2021 my interest for the Japanese culture has grown steadily. A year later I realized that a good knowledge of the language was required to improve my understanding. So, I started studying. In the early months my study plan was non-existent, and my approach quite disorganized. But over time, I realized that studying the language was a pleasant activity, and it has become a hobby. Meanwhile my goals and ambitions have evolved, and spending time in Japan in the future is one of the entries on top of my todo list! Thus, being able to understand the language to a certain degree is a necessity.

The JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) is widely recognized as the gold standard to attest one's ability to comprehend Japanese. It has five levels N5 to N1 (the highest), so it's also a very good way to measure one's progress. I'm currently studying to reach the N3 level (roughly speaking, the intermediate level), and well, it takes some time.

After taking the N3 exam on December (and likely failing it), I'd like to share my experience as a full-time worker and self-study learner.

In this post I'll describe how I prepared for the test, explain the choices I made, and how I tried to speed-up the process using Emacs.

A bit of context#

Before jumping into the details, I think it's useful to share some background info.

About me#

I work full-time as a researcher (software/security area), I have never taken a Japanese course at university, and I'm building my knowledge from scratch. I started studying Japanese in early 2022, using Duolingo to learn the basics of the language such as Hiragana, Katakana and common kanji. Around March/April I started studying with Genki I and Genki II (only the textbooks, not the practice books) to prepare for the JLPT N4. I attempted the N4 in July 2022, achieving 80 points over 180 (90 are required to pass).

About the language#

If you are not familiar with Japanese, there is something else you may be interested to know. Japanese is very different from Romance and Germanic languages. Just to mention some differences:

- in Japanese the subject is often omitted, and needs to be inferred from the context. For example the sentence 食べる, may be translated to "to eat", "I'm eating", or "As for them, eating";

- words are not typically written using a limited set of characters (i.e., the alphabet), but are rather built grouping kanji. For instance 食物, which means "food", is formed by 食 (food, meal) and 物 (thing, article). There are thousands of kanji;

- there are different levels of politeness, so something must be said or written in the proper way depending on the role, age, or social status of the parties involved. お待ち下さい and 待って both mean "wait", but the first is more formal and more gentle.

About the JLPT#

The JLPT can be quite difficult depending on the level. In general, it is divided into three sections:

- Language Knowledge (Vocabulary/Grammar),

- Reading,

- and Listening.

To pass the exam, a minimum score for each section, along with a minimum overall score must be achieved.

Each section has its own difficulties, like the ability to recall in the Vocabulary, or the rapidity of the dialogue in the Listening. I found particularly hard the sentence composition exercise in the Grammar, in which a meaningful sentence must be constructed given 4 parts. The reason is that in Japanese there are many particles and patterns, and the positioning of a particle can completely alter the meaning of the whole sentence.

Set the goal to N3#

After taking the N4 exam in July, I was quite satisfied. Even though I was aware I didn't prepared it thoroughly, I was able to understand many questions and large parts in the dialogues. So, regardless of the outcome, I decided to step up to the N3 the following session, since let's be honest, N4 ability is pretty limited. I remember I thought something like: "It will be hard, but what do I have to lose? My goal is to reach the N1 level, eventually".

Book and first difficulties#

Since I struggled with grammar during the N4 test, I decided to buy an in-depth grammar book to prepare for the N3. After reading some online blogs, I decided to go with the New Kanzen Master N3, and ended up buying the complete set. The set comprises 5 books: Listening, Grammar, Kanji, Reading Comprehension and Vocabulary. I took 2 weeks off, then started studying around August. I was very happy with my purchase, the quality of the book is astounding, to give an idea you can find grammar notes like this one explaining the use of particles: After ~ (verb), suddenly notice ... (with slight surprise). However, I also encountered the first difficulties; the books were quite demanding and I didn't know how to use them properly. As a self-learner, I didn't have the support of a teacher, and every time I had a problem, I had to (try to) translate the content myself. I know it may sound commonplace but, I couldn't do this properly without a desk and a PC. Basically, this meant I couldn't study while commuting or during the lunch break, I could only do it the early morning, after dinner, or on Saturdays and Sundays. I had to find a smarter way of studying.

Exam preparation#

The first thing I did to improve the situation was calculating the time I really had available. Given my study pace, there was no way I could complete the Kanzen Master in time, so I carefully pondered the chance of failing the test in December. My first decision was to reduce the overall study material I had to process, so I put aside the Reading Comprehension and Listening, and focused only on Kanji, Vocabulary, and Grammar books. I don't recommend doing this, as I don't recommend to shorten practice, but it is a reasonable compromise if you no longer have the time you had when you were a student.

The second thing I did was taking a lot of notes. My approach was risky and notes could have been reused for the second attempt (yeah, I may had already realized). Notes are very convenient, plus they can be consumed during breaks, on the smartphone, on the Kindle and so on. Emacs has this package called Org Mode, which is very powerful and I have been using a lot at work. To me, writing in Emacs with Org Mode and my Ergodox Ez keyboard is truly fun and I tried to take advantage of it (you may call it gamification).

The approach I was following was working, and I could track my progress weekly, but there were unfruitful weeks. I think this happened for two reasons: 1) it was a repetitive task, and not all the evenings or weekends I was inclined to do it (interesting weekend projects are a great source of distraction for a programmer), and 2) I was staring at the monitor for too many hours, so my back and eyes sometimes hurt. The only way I found to solve this issue was taking long strolls two to three times a week, and to stay productive during this activity I started listening to the JapanesePod101 podcast. I wish I added JapanesePod101 to my routine earlier, I find it so effective, and also relaxing.

I also tried other methods like the Anki memorization app to utilize short breaks and commute time. Many use Anki regularly, but for me it didn't work. I think flashcards are good to review stuff you have already studied, but they are not as powerful as notes. With notes you can add to each kanji useful info such as the meaning (kanji's true power), usage info, short passages, and so on. To me, reviewing flashcards was just a boring activity.

But wait, what did I do concretely? What are the advantages in using Emacs? And what a programmer can do to boost productivity?

Study as a programmer#

As explained in the previous section, my study was built on notes. But what do I mean by that? What did I do to produce them efficiently with Emacs?

Setup Emacs and Mozc#

Well, let me go back just a moment. When you study Japanese you encounter new kanji continuously. Each kanji has a precise meaning, but can be characterized by many pronunciations. Books use Furigana to support the student, a reading aid consisting of smaller Hiragana characters printed either above or next to the new kanji. Now, if you don't know a kanji but know how to read it thanks to Furigana, you can also write it on an electronic device, this means that you can look it up quickly on a dictionary. So, even if you don't have a Japanese keyboard, the most important aspect to take notes rapidly is to be able to write comfortably on the same document in English and in Japanese (leveraging Furigana).

To do this you must first install the Japanese Language support provided by your distro (in my case Ubuntu). Then you need a Japanese Input Method Editor. The solution is Google's Mozc. To use Mozc with Emacs you need to install emacs-mozc, a package that provides the Elisp files to run Mozc server. Lastly, you need mozc-mode, the minor mode to input Japanese text in Emacs. Since I use Ivy, a generic completion fronted for Emacs, I find convenient to set the mozc-candidate-style to echo-area.

Here's my configuration with use-package.

;; input Japanese

(use-package mozc

:ensure t

:config

;; set kana map type

(setq mozc-keymap-kana mozc-keymap-kana-101us)

;; set overlay style to default

(setq mozc-candidate-style 'echo-area)

)

;; toggle mozc mode

(global-set-key (kbd "<f7>") 'mozc-mode)

Let's see how to write Japanese and English on the same document with Emacs.

As you can see from the animation, hitting <f7> starts the mozc-helper-process, and subsequent input keys are immediately converted into Hiragana. The Japanese sequence input is underlined by the minor-mode, which simultaneously queries the Mozc server on the background to get the proper completion candidates. Candidates are shown in the echo area, the proper one can be selected with TAB or via numeric input, and then inserted at point hitting Enter. Hitting a second time <f7> toggles mozc-mode, and the subsequent text (I eat apples) is input using English letters.

To write English-origin words you need to use Katakana. To do that you input Hiragana, then convert to Katakana using the japanese-katakana-region function (as shown below).

Taking notes#

Any software can be used to take notes, but none provide the flexibility of Emacs. Emacs has built-in support for Org Mode, a major mode for keeping notes, maintaining to-do lists, writing computational notebooks, planning projects, and many more. I think there are two key advantages in using Org Mode over standard WYSIWYG editors like Microsoft Word: 1) you work with plain text files rather than custom or proprietary formats, and 2) Org Mode provides native support to convert your notes into other representations like PDF and HTML. Point 1 is super important as it allows you to use standard search programs like grep or ag against your collection of documents. Point 2 can be leveraged to display your notes on other devices, basically this permits to transfer notes on the smartphone or on the Kindle, without compromising readability (more on this later).

I relied heavily on tables while taking notes. To give you an example, I used tables to associate the Chinese and Japanese reading to every kanji, along with the actual meaning. Org mode has powerful table editing support, providing functions such as auto-alignment when TAB is hit, and in-cell content alignment via annotations. Also, it provides functions to globally customize table font (see below).

Productivity tips#

Emacs provides many convenient little features to improve productivity. Many are built-in, other can be implemented with simple Elisp functions. Here I'll show you some of them.

Expand-region: a function to increase the selected region by semantic units, a very convenient feature when you need to select text blocks. I bound it to C-=. The gif shows what happens when the C-= is hit repeatedly.

Copy-from-point-to-end-of-line: a function to that copies the content between the point and the end of the line.

(defun ddcteol/Copy-To-End-Of-Line ()

(interactive)

(save-excursion

(kill-new

(buffer-substring

(point)

(point-at-eol)))))

(global-set-key (kbd "C-c w e") 'ddcteol/Copy-To-End-Of-Line)

Demo (set the point to 私, copy to the end of line, then yank)

Expand-region and Copy-from-point-to-end-of-line are extremely useful when the extracted content is copied to the system clipboard. For instance, I usually:

- copy something to the clipboard:

M-w, orC-=+M-w, orC-c w e+M-w, - open Google Translate (Japanese->English):

S-s, - paste from clipboard:

C-y, - close the current window:

S-q.

It's not easy to translate something quicker than this!

Rectangle + Multiple-cursors: rectangle commands operate on a rectangular area of text, while Multiple-cursors is a package to operate simultaneously on different lines. See how you can work on 4 lines! (reversed demo, since mc breaks gif-screencast)

Register-based-jumps: when working with notes I frequently need to edit two tables repeatedly. The pattern is simple, add a line to the first one, then a line to the second one and so on. Going back and forth between two positions is a tedious activity. Fortunately Emacs implements registers, which are compartments where you can save text or positions for later use. So, I wrote a couple trivial functions to jump between two points A and B. It may seem silly, but it saved me lots of time with tables hundreds of lines long. Look at the gif to see how it works.

Exporting notes#

Up to now we have seen little functions useful to improve writing experience, but here comes one of the big advantages of Org: exporting notes.

HTML. Many devices have a browser, so a thing worth doing is to export notes to the HTML format. Org has a built in function to do that, org-html-export-to-html. You can call it with C-c C-e h h from an Org buffer. The HTML file produced has no style by default, but a CSS file can be embedded using Org TAGs. The same can be done to adjust some options, like the removal of the link used to validate the page, or the removal of author's name, etc. Here's a snippet from my notes.

#+HTML_HEAD: <link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="style.css" />

#+OPTIONS: num:nil

#+OPTIONS: toc:nil

#+OPTIONS: author:nil email:nil creator:nil

#+OPTIONS: org-html-validation-link:nil

I added a couple of settings to the CSS file so to use a dark theme and improve a bit the readability. Take a look at my vocabulary notes.

Hitting C-c C-e h h feels a bit slow, wouldn't it be better to use C-~? Well, I wrote a couple of functions to do so.

;; placeholder to execute a function by name

(defvar callable-function-placeholder "initialize function name"

"Name of a function callable with dd/... utility.")

(defun ddscfn/Set-Callable-Function-Name ()

"Sets the value of the variable callable-function-placeholder."

(interactive)

(setq callable-function-placeholder

(read-from-minibuffer "Set callable-function-name: " callable-function-placeholder)))

(defun ddccf/Call-Callable-Function ()

"Calls the function name saved in the callable-function-placeholder variable."

(interactive)

(funcall (intern callable-function-placeholder)))

(global-set-key (kbd "C-~") 'ddccf/Call-Callable-Function)

Here is how to use them. First I call the function Set-Callable-Function-Name specifying org-html-export-to-html as argument, then hit C-~ a couple of times, each time converting the note into HTML.

Android app. It was at this point that I realized I could use short breaks and commute time to review some Japanese! To do that I wrote a simple Python script to collect all my notes and generate an index page. Then I developed a simple Android application that leverages WebView to render the website, finally side-loaded the app on my phone.

I used a Makefile to automate the process, so every time a new note is created:

- the website is refreshed to take account of the new material;

- the website is embedded into the application local storage;

- the application package is built using

Gradlew; - the apk is aligned and signed with

zipalignandapksigner; - the apk is installed to the emulator (or the device) via

ADB.

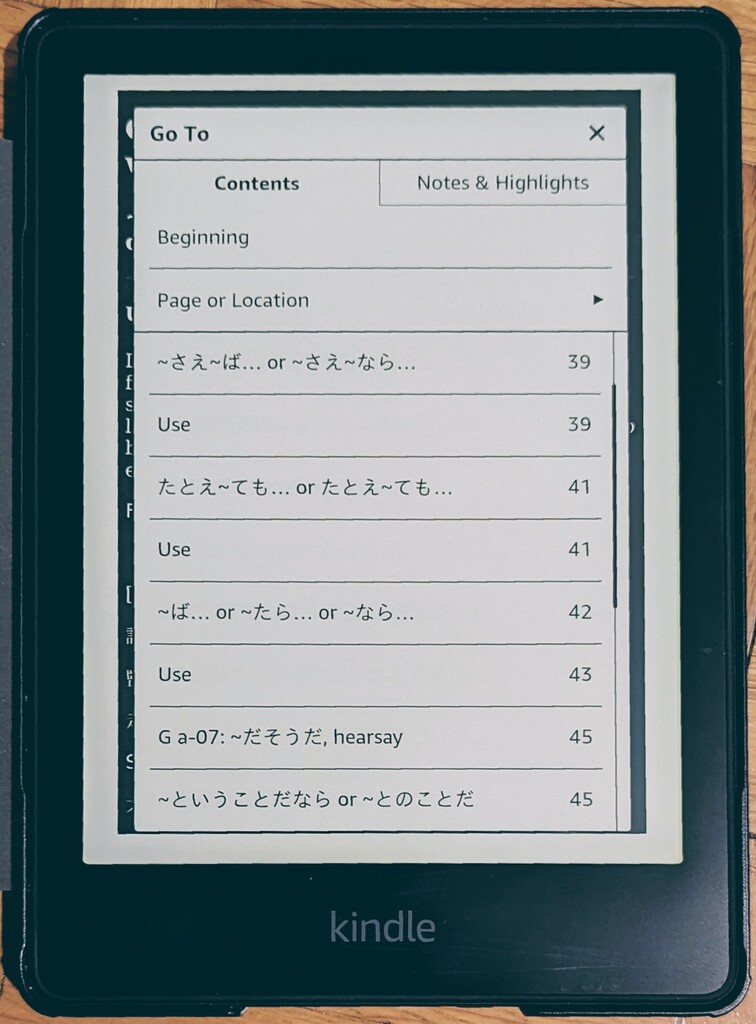

PDF, Kindle. Having the notes on my phone was great, but nothing beats an E-Ink screen when it comes to eye strain reduction. So, I needed a way to convert the material into PDF to send it to the Kindle. Org Mode supports Org to PDF conversion (the note is first converted into a LaTeX document, then into PDF, see the org-latex-export-to-latex function). The conversion works really well with structured documents such as articles and reports, but it wasn't the case for my notes (I didn't have chapters, or sections). The best solution I found was WeasyPrint, a package that gets an HTML source as input (usually code documentation) and turns it into PDF. Since WeasyPrint takes some time to produce the output, I wrote a simple Python script to generate the A5 format PDF representation of each note in parallel, then merged the PDF sources with pdftk. I'm quite satisfied with the result, links between pages no longer works, but every note file appears in the Index properly.

Exam#

As anticipated, I took the N3 exam on December, the 4th. A couple of weeks later, it's time to wrap up and make some reflections.

Some stats. I have created 91 well formatted Org notes based on the content of the Kanzen Master Kanji, Vocabulary, and Grammar books. Each file is 143 lines long on average. It took me about 3.25 months to prepare the material (August, September, October, and the first week of November). So, I spent roughly 3 weeks reviewing the notes before the exam (I was able to review more or less 40% of the material). As mentioned earlier, my preparation also included listening to all the lessons in the JPod101 N5 and N4 pathways (roughly 190 lessons, each 14-18 minutes long), and just 13 lessons of the N3 pathway (exam preparation unit). All the lessons were listened once (no review in this case).

N3 exam. I struggled a lot during the exam, and already during the first half an hour, I realized I was still far from the N3 level (at least, far from passing the test). While I was able to detect many of the patterns I had studied, Vocabulary was the real problem. Japanese is not like a Math or Coding questions, where you can use your reasoning or logic to find a solution to a problem. Indeed, it is very difficult to grasp the meaning of a sentence in which you can't translate 2 to 3 words. Also, I had a bit of trouble managing the time, simply, I couldn't read fast enough. This was a problem in pretty much all the sections of the test, including Listening (i.e., to select the correct answer).

Reflections#

You might be thinking, did it really make sense to prepare the exam this way? Wouldn't it be better to simply follow the advice of a teacher or go to a school? Are you sure you saved time using Emacs?

Short answer. Well in short, I think my choices were rational, and yes I still think my approach makes sense. But let me elaborate a bit more. The Japan Language Education Center estimates that students residing in Japan (and with no prior knowledge of kanji), on average, need to study 575-1000 hours to pass the JLPT N4, and 950-1700 for the N3. Taking notes took me about 110 hours (I use Emacs logbooks to keep track of time, so this number is quite accurate), while I have listened to JPod101 for at least 60 hours. So, the road is still very long. Anyway, I believe notes will give me a powerful advantage, since I will be able to review kanji and Grammar efficiently in the next months.

About time. Looking back in time, my guess to reach the N3 level in 4 months was too optimistic. I mean, a motivated student can definitely do that, but a full-time worker, according to my experience, can't think to allocate more than 8-12 hours per week to the task. Personally, I tried to boost my productivity reviewing stuff during short breaks, or listening to JPod101 while walking or before going to bed. But frankly speaking, at least half of the time I spent taking notes was during the weekend. This had quite an impact on my routine (less coding, less YouTube, etc.).

The errors. While preparing for the test, I think I made a couple of errors. The first one was try to process too much material, too quickly. For instance, the N3 introduces 370 new kanji compared to the N4, and I tried to study them all together, but it would have been wiser to slow down the pace. The second error was practicing too little. Reading speed is very important, and I didn't do anything particular to improve it. There are two apps that could help fixing these errors: Kanji Study and Todai news. I've been testing them recently, but unlike JPod101, I probably need using them a bit more before recommending.

What I learnt. Learning the Japanese Language is a hard task, not in the sense that it is something complex, but it requires time. However, this activity is offering me a completely new perspective, and I think it has already affected the way I work. While I was studying at university I used to organize my schedule based on deadlines, and the goal was always try to maximize a score, or get the best grade. Now I tend to prioritize efficiency, so I try to destructure big tasks into smaller ones, develop a routine, and track the progress weekly.

What will I do next? In the short term I'd like to improve the quality and expand my notes, there's a lot of material in the Kanzen Master that I haven't processed yet. Also, I'd like to practice writing, just to test whether I can more easily remember kanji (yes, even though I can read and speak to a certain degree, I still can't write using a pencil). After consolidating my background a bit, I will try to add more balance to my preparation, probably trying to read short articles. I'm still a bit embarrassed to try to speak to someone in Japanese, but maybe I'll be ready to ask the help of a teacher in the next moths.

So, if you are a programmer, and would like to study the language, don't be too worried, I'm really enjoying the journey!

I hope my experience will be useful.

Thanks for reading.